All right, nanowrimo people: it’s that time again.

The first five days were kind of wild and crazy — you didn’t really know what was going on in the story — the characters were sort of running around going “Look what I can do! No, me! Look!” and you let them have their head and run it out.

The next seven or so days, we got a sense of what was going on and where the thing would take us, and that sense of purpose and vision imparted a lot of fire and motivation to the writing. If you’re lucky, you’ll be able to ride that right down to the point in a few days when you realize that a bunch of your favorite people need to die.

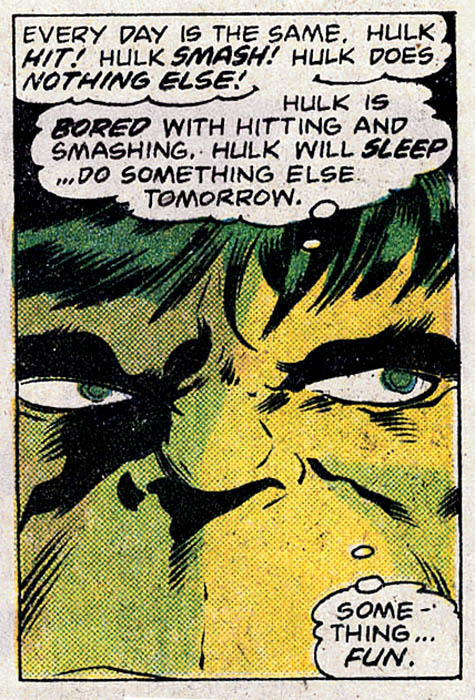

However, that’s if you’re lucky. In other cases, you’re at this point where… well, things are happening, but you’re not sure if they’re going anywhere. In fact, you’re not sure if the story is going anywhere. Your loved one comes into the room where you’re sitting and looks at you for a few seconds and then says “how’s the story coming, hon?” And you’re like:

You sit down at your desk to get another couple scenes down, read the last line you wrote, think about what should happen next, and:

Pretty soon, it’s time to go pick up the kids and you’ve written all of a forty word paragraph in which the main character sits around thinking about how he doesn’t know what to do next.

Doubts start to creep in. Maybe 50 thousand in 30 days is just too much. Maybe you already told the one good story you’re going to tell. Maybe you’re brain is broken. Maybe this thing is going to be no good. Maybe it’ll be actively bad — the kind of bad where you give the finished draft to some friends to read and their feedback is basically:

I’m not going to make you feel better about that. It’s (theoretically) possible that all those doubts you have are grounded in indisputable fact — maybe one of your friends is one read-through away from a horrible disfigurement — I just can’t say.

But here’s the thing: none of that matters.

I’m going to have to get a little Midwestern on you now; that’s just who I am.

When I was growing up and going through junior high and high school, I was involved in a lot of extracurricular activities. A lot. First chair in band. Marching band. Jazz band. Choir. Swing choir (yeah, glee, whatever. shut up). Oratory/Debate. Drama. Newspaper. Yearbook. Football. Basketball. Wrestling. Track. Was there more? I think there was, but it’s all kind of a whirling haze.

In the parlance of the region, I “kept busy”.

You might say I dabbled in a lot of things, and you’d be right: with the exception of the music stuff, everything just kind of came and went with its appropriate season. My folks had a very simple rule for any of these projects: I could try anything I wanted, but if I decided (after the first serious introduction) to keep going with it, I had to finish it. Period. No exceptions. Every time I signed up for something, it meant rearranging schedules, figuring out who was going to get the car when, and generally bending everyone into pretzels to make it work. You want to do wrestling? Fine; you’re in it til the end of this season. Yearbook? No problem – but you’re not done til this year’s edition goes out the door. It didn’t matter if I lost every fucking match I ever competed in (I did), or if my particular style of prose was often very wrong for the yearbook (it was) — I was in, by god, and I wasn’t getting out til the bell rang.

So let me lay this out for you now: you’re in til the bell rings. It doesn’t matter if the story stinks, or you can’t think of an ending, or everything seems to be coming apart at the seams; you’ve asked your friends and family to bend around your schedule for the last three weeks, and if you quit now, you’re basically giving them a silent but nonetheless profound “fuck you” and walking off down the street, whistling a carefree tune. In short, you’re an asshole.

And, come on, you’re not an asshole. You’re tougher than a little bit of story ennui. You’re the kind of person who wants to finish up a story and set it in front of all those people who helped you get through the rough parts and say “This is for you. Thank you. It’s a little busted in places, but I think it’s a good start, and I can fix the rest.”

You can’t fix something you never finish.

You don’t really know if you like the game unless you stay in a full season.

A Few Tricks

All these “hoo-rah, you can do it” speeches are fine, but how about some actual concrete stuff to try?

If you’re feeling like you don’t like what you’re writing or where things are going, there’s things you can do.

- If things are sort of sans direction, make something happen that your protag has to make a decision about — not just react to, but actually make a tough decision about: do I save the bus full of children or my sister? Stuff like that. Hard decisions, preferably ones you don’t already know the answer to.

- Are you over-describing stuff? Stop. Switch to nothing but dialog for awhile. If you’re protag doesn’t have anyone to talk to, FIX THAT RIGHT NOW.

- Is the scene boring you? Drop it and skip to the next. Flag it with a [finish this later] and move on.

- Are you stuck on how to get through the current scene, but you’re writing a solution anyway? STOP. Go write some other scene — that reluctance is your brain telling you that you’re writing something stupid and that it will give you something not-stupid LATER. Write some other bit, and maybe that’ll even explain how to fix the other scene. Hindsight is actually useful when you can jump back and forth in time.

- If all else fails, attack the scene with genre-appropriate ninjas. I am totally not kidding. You’re writing a romance? Then genre-appropriate ninjas (GAN) might be an unexpected kiss from an unexpected person. Boom. Ninjas. Every genre has ninjas.

- Finally, every scene has conflict.

Get back in the game.

Don’t worry about falling down.

The best smile in the world is the grin on the player who’s covered in mud.