More than a few years ago, I was having a conversation with De Knippling (whom I met in college) about our mutual childhood history, growing up in the midwest. This was after both of us had moved away and, by happy accident, found ourselves neighbors again in Colorado. De was talking about the fact that there is damn little in the way of supernatural fiction set in places like Iowa and South Dakota. I, never willing to give a straight answer when snark will suffice, said “That’s because nothing magical ever happens out there. Ever.”

“Now that’s bullshit.” She gave me one of her ‘you’re being stupid right now’ looks, then hit me with a “Duuuuude.” You have to know De to really understand how she says this, but I will try to convey it by explaining that the word, as spoken by her, sometimes has three syllables.

I said nothing, but probably had one of those purposely-not-getting-it expressions on. She rolled her eyes. “You know better than that.”

(And she was right, of course. I did, but it’s not something one generally talks about.)

“In fact,” she leveled a finger at me, “I dare you. I double dog dare you to write a midwestern paranormal for you next story.”

So I did. More than a few years later, that story has an agent, and that agent is shopping it around with a couple publishers, and I have De and her double-dog dare to thank. And blame.

When I think of De, I think of her unflinching, untrammeled sight into the heart of a thing. She is an excellent critic, but equally able to see a magical, whimsical, childish truth that grownups try to ignore.

I asked her to drop in today and share her memories of growing up in that magically non-magical place (because I like hearing her say the stuff that’s in my head) and then I made her talk about how that background led to her writing a zombie outbreak book set in her current home town.

(She says it doesn’t at all, to which I can only reply “Duuuuude.”)

Doyce asked me if I wanted to write something about growing up in South Dakota. Of course I said yes; I’m trying to talk him into a project in January having to do with the Weird West.

We both grew up in the Weird West, really, although we grew up in slightly different areas. He grew up near a small town called Miller, South Dakota, and you can pick up other entries about it on his blog. I know that it’s affected the way he tells stories by a few of the things of his I’ve read.

I grew up slightly differently than he did, also in the middle of nowhere. I’ve been trying for years to explain what it was like, or why anybody should care, but what it comes down to is that it was a profoundly magical place, and not in a nice way.

It didn’t seem, at the time, like living five miles away from our nearest neighbor, eight miles away from the nearest spot on the map (Lee’s Corner, population 2), or having no running water at the school was magical, but it was. There is nothing out there. It’s like the Australian outback; it’s like Siberia; it’s even like a remote mountain in the Himalayas sometimes.

Only flat.

There was grass, and there was sky, and everything else was something that someone dreamed up. Trees aren’t natural; they’re a sign of people. Fences are a trail back to someone’s house. And houses are there only as long as someone tends them, day in and day out, like something fragile. Otherwise they’re a hollow gray shell that’s been stripped bare by the wind and the dust.

The wind out there’s enough to smother babies, just suck the air out of them, so you always cover their faces. It’s enough to pick you off your feet and throw you in the sky if you spread your coat wide. The coyotes are closer to you than your neighbors, and a lot louder. The blizzards kill someone every year, like a sacrifice to a very cold Hell. The summers kill, too, and you hide out in the basement, because air conditioning is only something you see on TV. You can see for about ten miles of grass in any direction, and it’s like being on an ocean, only you don’t get seasick. And the flies, the horror of the flies, the constant, awful crawling when the cattle are around.

And then there are these cracks in the ground, where water has run (yes, we do get rain, big deadly storms that set things on fire almost as often as they put them out). Most of the time, you can see them coming, but sometimes you can’t, and people have driven trucks or ridden horses right into them.

For the longest time as a kid, I had this secret fear that we’d go out into the fields during the summer and I’d lose my parents.

When my brother and I were very young, we were left in the pickup truck with books, water, and a cooler full of sandwiches while our parents drove tractors around. We would run around; as long as we were within earshot of the truck, we were okay. We’d make up stories, pick on each other, dig holes in the dirt–anything to pass the time.

I just knew that one of those cracks was going to open up under my parents. They would drop in, and the wheat would cover them up again in long, golden waves, and I’d never see them again, and I’d never know what happened to them.

I’ve tried, time and time again, to find a way to explain that feeling through a story–the nothing, the crack in the ground, the disappearing — but I’ve never done it justice. I’ve been trying to figure out how to phrase that in terms of a fairyland, in which the mortal realms and the fairy realms lie side by side, with sometimes tragic results.

The magic is close, very close. And, from the inside, it looks perfectly ordinary.

While I’m waiting for that perfect idea of how to do this, I write other things, of course. The idea that the magical is ordinary, even banal, crops up in pretty much everything I write. I know that people want to think of magic as extra-special, something that can lift their lives out of the ordinary, but I can’t help but write about the magic that people take for granted or adapt to so quickly that they forget it was ever magic. That’s what life is like now to me anyway–you’ve probably never noticed the magic of a stoplight, but I didn’t live in a town with a stoplight until I hit college. When I discovered the Internet existed, I cackled.

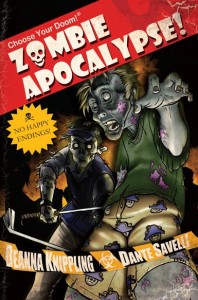

I have a book coming out now called Choose Your Doom: Zombie Apocalypse. It’s not about magic, of course; it’s all about zombies, and I don’t consider zombies to be magic–more of an odd type of SF. (This probably would be more obvious if Michael Crichton had written a definitive tale of zombie disease vectoring instead of The Andromeda Strain, but there you go.)

I have a book coming out now called Choose Your Doom: Zombie Apocalypse. It’s not about magic, of course; it’s all about zombies, and I don’t consider zombies to be magic–more of an odd type of SF. (This probably would be more obvious if Michael Crichton had written a definitive tale of zombie disease vectoring instead of The Andromeda Strain, but there you go.)

However, I did take the idea that a change big enough to rewrite the genetic material on our planet could be inserted in our lives and used it to show that we’d do more about it than run in terror and barricade ourselves in the nearest Impregnable Fortress. We’d use it as an excuse to steal comic books; we’d stick our fingers in it and see what it tastes like; we’d try to be heroes and end up almost ready to kick our refugees into the arms of the monsters because they’re that annoying.

And sometimes we’d even switch sides, on purpose, because that was the only way to get the job done.

Choose Your Doom: Zombie Apocalypse comes out at the end of November. Hot tip: if you preorder it here, it’s 15% off, which is apparently the only place that is true.

I totally don’t remember that, but, as you know, I have the memory of a sieve, so okay.

Thank you :)

Really? Yeah, Hidden Things is basically “De told me to.”

I grew up on the other side from Miller. For me South Dakota was/is a magical place. The low rolling hills are the bottom of an ancient ocean, if you kicked the dirt you’d find clams and other great shelled fossils that gleam when cleaned off. The glaciers ripped the mystery off of the east when they sent 700 feet of South Dakota to Nebraska.

One of my best friends in High School was direct descendant of Crazy Horse and is now a Lakota shaman. The keeper of the Sacred Calf Pipe was a good friend of my Mother when they grew up together.

I wasn’t in the middle of nowhere, Eagle Butte is along a busy two-lane highway, a central route between the Twin Cities and Salt Lake City, we had an airfield and were right under the bomber and tanker routes for Strategic Air Command.

I have wallpapers on my computer at work of a thunderstorm raging across a newly combined wheat field, people will say “thats really flat”. I reply with, no, thats Western South Dakota, Eastern South Dakota is the flat part.

If we’d not come to Alaska, we’d be in Sisseton right now, I really do miss it there.