I’ve got a post percolating about stories, games, and plot vs. character, but I’ll save that for tomorrow and instead point out that I wrote a guest blog over at ktliterary.com today: On Being Rexroth: Living with a Literary Agent.

I’ve got a post percolating about stories, games, and plot vs. character, but I’ll save that for tomorrow and instead point out that I wrote a guest blog over at ktliterary.com today: On Being Rexroth: Living with a Literary Agent.

Today, kids, it’s storytime.

But first (and related to the story), I’m going to revisit the Macmillan/Amazon Weekend Event and talk about publishing in general.

Now, Amazon came out yesterday with a statement about the whole weekend drama llama. Yes, they attempted to paint themselves, disingenuously, as “fighting for the little guy”, and I rolled my eyes, but I was surprised that most of the snickering and snide commentary from the internets was directed at their use of the word “monopoly” when describing Macmillan’s control over their imprints.

I was also kind of disappointed. The people doing the snickering are readers (and writers), and they should understand the meaning of the word well enough to know that it was perfectly apt.

Monopoly: exclusive control or possession of something.

Of course Macmillan has a monopoly on the books produced by their various imprints. It could not be otherwise. It’s not a monopoly in the “Ma Bell” sense, but that wasn’t the sense in which it was being used.

Does Amazon likewise have a monopoly on ebook sales?

Nnnnnnno. Maybe no. Probably not. They do not control ebook sales to the degree that Macmillan controls who gets access to Macmillan books.

But hey: it’s close enough that if someone said “Amazon essentially has a monopoly on ebook sales”, I would not bother to argue, because it’s not worth the effort and gets us nowhere. For the sake of argument, let’s say both Amazon and Macmillan both have “exclusive control or possession of something” that the other one wants some access to.

Ultimately, all that happened this weekend was Macmillan and Amazon fighting over which monopoly interest gets to exert their pricing desires, not whether. And the thing to remember about that is that pricing determined by a monopoly is, generally, never good for the consumer.

So who was I rooting for in that weekend fracas? Please: that’s like betting on a fight between two rabid weasels — I’d prefer they both lose. Amazon’s just trying to maintain their hold on epublishing and push Kindle sales, and Macmillan won’t earn authors one cent more by forcing Amazon to sell books for $15 bucks (they should, but only if the author has the sense to renegotiate contracts based on the change to the market Macmillan’s trying to push through), and their justification for the ebook pricing is an insult to my intelligence.

Who do I think will ultimately win? In the end, any of the Big Six publishers will probably come out ahead in a game of chicken with Amazon unless technology provides a new model for publishing, because publishers have more leverage as the content provider.

(Really, authors should have the most leverage of all as the true source of content, but that logic only works if authors acted in unison, which… well, come on. The most influential move most of us make in a given day is deciding whether or not wear pants.)

For me, all that this weekend did was remind me how much is broken with regard to the way publishing works.

Writers, whether published or not-quite-yet, please hear this: I need you to think like a reader for a little bit. I know you are readers. I know. Shh. Shut up and bear with me. This isn’t a trick: I’m not going to steal all your royalty checks while your eyes are closed. Just… think like the person who, at the end of the day, finally buys and reads a book.

Because here’s the thing: in the world of paper publishing, publishers don’t give a tin can fuck about you, the reader.

Please don’t think that I hate publishers for this. They are businesses. This is how the business works right now and, unless the technology available forces a sea change, it is how it will continue to work.

And please don’t think I’m lumping writers in with publishers. Writers (all those I know, and I know quite a few) love readers, even if they aren’t their readers. As I said, they are readers.

So, be that reader for a second. Let me help.

Let me tell you about Charlotte*.

Charlotte is one my coworkers. Charlotte loves to read. She doesn’t really read the same kind of stuff that I do, but we still manage to find lots of reader-stuff to talk about, because there’s a kind of commonality two avid readers can usually find.

Right now, Char’s having a pretty rough time. Like a lot of folks, she’s feeling the pinch of the recession: she traded in her much beloved, bright red vehicle for one with lower monthly payments; she and her husband are looking for a more affordable place to live because their current house is proving to be too much of a burden right now. She’s got a injury that she has to go to physical therapy for several times a week.

… and she has to deal with John*. John is old school. John doesn’t use Outlook’s calendar function – he writes down everything on one of those desktop blotter calendars and insists that be the ‘master calendar’ for his department, and that is just the tip of the iceberg of retrograde thinking that floats around inside his head.

(Note: that isn’t actually the master calendar for his department: every few weeks, someone takes his calendar and “manually syncs” it with the Outlook calendar EVERYONE ELSE uses, thus creating a viable electronic version… which he’ll never ever see. Which, come to that, he doesn’t even understand the need for.)

At Christmas time, Charlotte asked for one thing: a Kindle. As far as I could tell, everyone in her life pretty much chipped in and got it for her. Maybe she got some other things as well, but if so, I didn’t hear about them. She loves that thing, and she uses it constantly. Her lunch breaks are Kindle breaks. Her weekends (thanks to her injury) are pretty much “Kindle and heating pad” days. We’ve talked about Amazon’s DRM on the Kindle a few times, but the bottom line is that it doesn’t really affect her and so long as that continues to be the case, she doesn’t really care.

She just wants to read.

And, I think it’s safe to say, because of the Kindle, she’s buying more books than ever. Any writer would be lucky to have Charlotte as a fan.

Well, maybe.

Not if your ebooks cost fifteen bucks.

See, when I got a chance to talk to Charlotte after all this stuff that happened this weekend, the first thing I asked her about was her purchasing habits with her Kindle, because she’s the only person I know who uses their Kindle in the way in which it was intended. Kate uses one, but she uses it exclusively for work, which means reading partial and full manuscript submissions sent to her by authors. My agent also uses one, but pretty much in the exact same way. As far as I know only Charlotte uses it the way a regular reader does.

And Charlotte doesn’t buy fifteen dollar ebooks. Most of the time (are you listening, Amazon?) Charlotte doesn’t buy ten dollar ebooks. Given a choice between a book listed for five bucks and ten bucks (or the promo stuff available for free), and all other things (quality, subject, reader interest) being equal, she’s just not going to buy the ten dollar book. They’re both books, after all, reasonably well-vetted, and as I’ve said, she just wants to read.

“But,” cries the writer, “if I let Amazon list the book for five dollars (or four, or three, or two), I will make half as much per sale.”

Sure. Yes.

You know how much money you’re going to make from selling that ten (or fifteen) dollar book to Charlotte?

Nothing.

Because she didn’t buy it.

Cheap sells more copies — puts more copies of your story in front of more readers.

And maybe, juuuust maybe, authors should be more concerned with getting their stories to the greatest number of readers, instead of worrying about per-sale payoff.

Maybe publishers should be too, instead of clinging to the old publishing model in which their real business is selling paper.

In the postscript to this piece, Eirik Newth India, Ink. explains why Big Publishing consistently cites costs to create ebooks that fall miles outside my experience and expectation.

Short version: they’re doing it wrong.

Long version:

Publishers are still producing paper books the “X-Acto–and–wax” way and then outsourcing their e-book production to other companies, which probably automate the conversion process, and then they’re not practicing any kind of QA on what comes back, because nobody gives a shit, because the people who make the decisions don’t read e-books.

No wonder they think making an ebook is an expensive, time-consuming process.

Yes, you read that right. Publishers aren’t producing workable electronic files when they produce a paper book — their product essentially has to be OCR’d by a third party company to get an ebook out of it. They start with a hardcopy difficult-to-translate template file and make someone else turn it into an electronic version for distribution; a version they’ll never read.

They are, in short, my coworker John.

John’s on a ‘planned retirement’ schedule that concludes in a little over a year.

People are counting. the. days.

Draw whatever parallels from that that you like.

I have a basic business writing and grammar class to teach today, so this is short, but I wanted to toss it out for discussion.

This spun off of a conversation I was having with my wife. For those of you who don’t know, Kate’s sekrit superhero identity is Daphne Unfeasible, the mastermind behind ktliterary.com, a literary agency that focuses mostly on YA (Young Adult) and Middle-grade fiction. Those types of books (and, to an extent, the individuals within that target audience) are a passion for her, one which I fully support.

But (as I said while sitting around at my family’s place over Thanksgiving) “YA” as a category of books kind of bugs me because from my point of view (as a consumer and as someone who catches very random snippets of agenting talk when I pop into Kate’s office to ask if she’s seen my shoes), the question of whether or not a book is YA (or middle-grade) pretty much boils down to “how old is the protagonist?” If the protag’s about the right age to fall within the target audience of such books, and the subject matter isn’t too dark, then you’re YA.

(Yes, I know I’m oversimplifying the process. I know. I KNOW. Understand that this is my perception as a consumer, not someone ‘inside’ YA. I will concede that I don’t know as much about the inner workings of the YA publishing industry as someone inside it. However, while I’ll concede that, I’d also like to point out that since I (the consumer) am the one spending money on the books, my (limited) perception matters just as much, if not more, than the people who know all the nuances.)

Anyway, back to the story. I was saying that it bugged me, because the whole thing just kind of seemed like cheating. I think I said something like “The genre of YA is basically nothing more than an age bracket. It’s sloppy.”

To which my super-keen wife said “Sure, it would be, if that were the case, but YA isn’t a genre.”

Then we argued about discussed that for awhile, and the fruitful result of that conversation looked something like this.

(This presupposes the fact that YA as a category-if-not-genre of books is a hot publishing commodity. Generally, that’s true.)

Here’s what I meant by that middle bullet point. Take a look at your local book store. Look at those signs over the book shelves. Mystery. Suspense. Literary Fiction. History. Science Fiction. Fantasy. Romance. Travel…

… and Young Adult.

There, all by itself, with no subheadings to be seen, are all the books aimed at YA readers, lumped together. Sweet Valley High rubbing up against Twilight. Thirteen Little Blue Envelopes next to Two Minute Drill. Catching Fire halfway down the shelf from Diary of a Wimpy Kid.

Dogs and cats, living together. Mass hysteria.

Or, possibly, genius.

See, if I’m browsing for books in the local store, I go to the genres I dig, right? For me, that means I go poke around in the Science Fiction and Fantasy section for awhile – a couple hours, whatever – and then I’m pretty much done.

The odds that I’m going to run across an interesting biography during that time? Low. The same goes for randomly picking up, reading the cover copy on, and buying No Country for Old Men, or the latest hot suspense thriller. Not going to happen. One of my coworkers is a huge Stephen King fan. Huge. Until I mentioned it last week, she had no idea he’d written On Writing. Why? It’s in another section of the store.

Over in the YA section (of the bookstore or amazon.com or whatever), the odds of that sort of thing happening — cross-genre pollination, if you will — are exponentially higher, simply because everything is lumped together.

Let me tell you about me-as-a-young-reader: I was a slut.

William S. Burroughs? I was there. Random “sports” novels? Sure. Catcher in the Rye? Yep. Alfred Hitchcock collections? Of course. Stephen King? Heck yeah. Trixie Belden? All 34 books in the series, baby, and throw in the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew as a snack, and chase the whole thing down with The Lord of the Rings (read 15 times during high school). Then the Old Man and the Sea for dessert.

Today? I pretty much stick to my genres of interest.

Why? Well, mostly because I don’t see the other stuff.

But the YA readers see stuff from all different genres. Moreover, they pick up, check out, and decide to read stuff from all different genres. Because it’s there, and ultimately they are readers and they (like the grown-ups) just like good stories.

I don’t think I’m any less voracious a reader than I was as a kid. I don’t think anyone is.

But I think we read less broadly than we used to, because as we age out of the YA area, our reading selection gets segregated.

Then we buy less, because we’ve ‘read everything’.

Maybe, just maybe, all those subsections in the grown-up section of the book store are stupid. Maybe.

I’m not sayin’, I’m just sayin’.

Yesterday’s post generated a lot of interest. And emotion, yes, but mostly interest. If I can be allowed to revisit that post for a second, I’d like to sum the whole thing up like so:

Ignore questions of infrastructure and the costs of ebook file development; those things are tangential to the current issue. What Simon & Schuster, Hachette, and HarperCollins are doing by delaying release of ebooks has nothing to do with those issues. It is about money. Period. It’s either about pushing readers toward the purchase of hardbacks, like the good old days, or it’s about the shoving match going on between Amazon and the Big Six over the price of ebooks. Either way, it’s about money.

However, the tunnel-vision focus from the Big Six on that single issue means that they are missing something critical: by delaying the release of official ebooks, they are creating an environment in which ebook piracy (thus far, a negligible issue) can and will thrive. This will hurt them, and I believe they will transfer that pain – which they caused themselves – to their authors.

This makes me angry.

There. That’s all of yesterday TLDR post, in three paragraphs. You’re welcome.

Now then.

Generally, I try to avoid pointing out a problem without proposing some possible solutions. Doing otherwise is what the kids these days refer to as a “dick move”.

So:

What could the Big Six do, with regard to the release of ebooks, that would be better than the idea they’re currently going with?

As I said yesterday:

Some folks asked me yesterday what I thought of James McQuivey’s idea to delay the ebook-as-a-separate-thing by four months, but also give it away as a free thing with every purchase of a hardback edition. I think it’s a great idea. I thought it was a great idea when I suggested it to my agent about six months ago on Twitter. However, I won’t take credit for it – the indie gaming industry has been doing that for years; as a smaller, more nimble publishing organism, it has already felt and adapted to the changes of the digital age, and could teach the ‘real’ publishing world a thing or two about what works and what doesn’t.

I told Joanna Penn in an interview last year that the tabletop role-playing gaming industry started out by trying to model the methods of traditional publishing, found out the hard way that that really didn’t work for them (in the long run, it’s not working for big publishers either, but they’re BIG, so they didn’t notice as soon), and had to find new solutions. They were the first to adopt electronic publishing, shame-free POD printing, electronic-only publishing, podcasting-modules, mixed media releases, and every other experimental method anyone could think of, good or bad. That’s fine: they’re small, and experimenting is something small groups of people can DO that big groups can’t.

But what that means is that they’ve come up with some things that consistently seem to work, which, to a greater or lesser degree, might translate into solutions for Big Publishing that would please even the greedy bastards longing for the golden profits of yesteryear. I don’t have much time, so let’s get right to it.

Package the ebook with the hardback as a value-add

This works. More to the point it IS WORKING. Not just in gaming, but on Amazon, with the Kindle. For gaming examples, go to indie press revolution and take a look at the options for games like Penny for My Thoughts, Spirit of the Century, or Mouse Guard. I’m not going to discuss this further; this is the granddaddy of ‘new’ ideas, and dead-fucking-simple to implement.

Subscriptions

Whazza? Subscriptions?

Eleven million WoW players tells me that this is a sales method that can work.

Take a look at Paizo.com. They have a brilliant kind of deal set up for all their games and plain-old books: set up a subscription to one of their channels (like Planet Stories, which is your classic pulp “planetary romance” stuff). It costs you X dollars a year or whatever. Every month, you get an email about the new releases within that “channel”, on ebook. NEW releases. If you decide to buy, you get 30% off the unwashed-masses price. (Edit: Or hey, you get it on day-of-hardback-release. Even better: Both.)

Or, how about the Big Dog of gaming, Wizards of the Coast? WotC has done some stupid stuff with regard to PDFs of their products in the past, but DnD Insider is smart. Pay for a monthly subscription to the service, and you a couple magazines every month with articles and useful stuff, written by the names you’re already fans of, some cool apps, and ‘free’ access to every one of their current books, as searchable PDFs. I’m not a member, but I gather that members also get access to ‘preview’ copies of upcoming books, months before they’re released, which generates stir and interest and maybe a few advance reviews posted on —

Oh, you know what that sounds like in publishing? Advance Reader Copies (ARCs).

Yeah: “Sign up for our monthly subscription, and get digital ARCs of our upcoming titles, and a discount on the REAL digital copy when it’s released.” What book nerd wouldn’t jump at the chance?

The Ransom Model

There are a couple game designers who do stuff like this, notably Greg Stolze and Daniel Solis. There are a couple different ways it gets implemented. With Stolze’s Reign supplements, if Greg collects enough money from contributors (the “threshold pledge”) he releases the ebook as a free download for anyone and everyone. An easy tweak for this in Big Publishing works like this: “If we get enough preorders for the ebook, we’ll release it the same day as the hardback comes out. If not, you have to wait.” I like this, because it lets consumers tell publishers what they want — a ransom model works pretty well as a market study — the consumer has power, and if they don’t exercise it, the publisher feels justified in delaying release.

I can’t help but note that this is a pretty workable thing for indie authors. (If you don’t want to take preorder money for something you might not end up doing, run it like a publish-athon and just take pledges — it’s still a good a way to gauge interest.)

You can also reward the ransom-preorder people in lots of fun ways. A thank-you list on the website or inside the book, mentioning people who helped make that version of the book happen when it did. A unique cover for the advance-order people. Hell, I dunno – what else would be cool?

That’s stuff off the top of my head, stolen from people who are making it work in gaming (and thanks to Chris Weeda for the suggestion).

The important take-away is this: ideas and implementations vary, but they all have one thing in common: they require embracing e-publishing, not holding it at arm’s length like a used condom you found in the spare sheets for your hotel room.

Embracing it. That’s the first thing publishers need to do. That’s the first step.

Right now? I’m not seeing it.

And that’s not a problem anyone but the publishers themselves can fix.

(In which I probably guarantee that I won’t be published by Simon and Schuster.)

Preface

I waited a day to talk about this, because I was pretty mad and ranty about it yesterday. Having given it a full twenty-four hours and evaluating my internal gauges, it turns out that I’m still angry, and that is not likely to fade, so there’s no point in postponing the discussion further.

Because I’m mad, this post may meander a bit. I will edit it as much as I can to make it coherent, but no promises. Don’t hate me for THAT, at least.

Points of Reference and Context you will Need

Yesterday, Simon and Schuster (a fairly major book publishing company) announced that they will be delaying, by four months, the electronic-book editions of about 35 leading titles coming out early next year.

(Hachette, another publisher, also announced plans along these lines, but I’m focusing on Simon and Schuster’s statement because Hachette only announced their intent to do so, not the concrete plan — in other words, they might still back out, and ‘we might do this too’ isn’t news to me.)

(Update: HarperCollins is on the same bandwagon.)

Giving credit: this story was linked off twitter by James McQuivey, who wrote about it at length on the Forrester Blog. It’s a good read, and (necessarily) polite enough that no one’s likely to lose a client over it. If you want a polite assessment, I recommend his.

(Egregious oversight: my amazing wife wrote about this yesterday on her agentry blog, and got a good conversation going there as well.)

Anyway. @glecharles (Guy L. Gonzalez) linked it on twitter, which brought my attention to it, and Rob Donoghue (whom I’m not going to link to on Twitter because his page is privacy-locked, but whom I respect immensely) summed up my immediate reaction with this comment:

Simon & Schuster and Hachette – doing their part to guarantee ebook piracy becomes the norm.

If you don’t see the point Rob’s making, give me a minute – I promise I’ll get to it.

This whole thing is essentially a straight-up counterattack aimed at online retailers like Amazon who are selling the ebook copies of best sellers for “only” $9.99.1

See, those $9.99 sales are actually costing Amazon about five bucks per sale. Get that? Amazon is losing money on every bestseller Kindle ebook they “sell”2 right now. Why are they doing this? Simply, to set consumer expectation for a lower price point on ebooks and to use that as leverage to force publishers to sell ebooks for a price somewhere in the same hemisphere as ‘sane’.3

Now, I’ll give S&S props for honesty; they are very up front about the reason for this decision: money. From the WSJ article:

…taking a dramatic stand against the cut-rate $9.99 pricing of e-book best sellers.

“I can’t sit back and watch years of building authors sold off at bargain-basement prices.”

Simon & Schuster has high expectations for the 35 titles involved, all of which either have large printings or are expensive.

[P]ublishers have come to fear that the bargain prices will lead consumers to conclude that books are worth only $10, or less, upsetting the pricing model that has survived for decades.

Ms. Reidy said she is concerned that e-book sales are cannibalizing new best-selling hardcovers.

“What horrors,” cry publishers. “Ebooks only cost us a tiny, tiny fraction of the money required to print, ship, store, and physically stock hardback copies of our books, so those evil, evil people-who-are-not-us actually want us to charge proportionately less money for them! Woe. Woe!”

What greed. What myopic planning. What longing for an unrecoverable, pre-digital past. What mewling.

And worst: what foolishness, to force your customers to steal from you.

Let me explain how easy it is to create a digital copy of a book. Almost anyone I know can do it in less than an hour with tools readily available.

I now have a digital copy of the book, saved to my computer. With a few more button presses, I can format it for pretty much any ereader on the planet, but it’s probably already a PDF, and thus accessible by nearly anyone. If I want to get fancy (and that’s a big if) I can run Optical Character Recognition on each page of the scanned document to make it a truly scannable, searchable document, but I don’t need to – I already have a readable copy of the book.

…which I can flag with a few tags and share via any one of a thousand various methods largely impossible to trace back to me.

That whole process took me less than an hour. I am, at best, merely competent with a number of introductory-level tools available to me for such a task. I don’t do this. Moreover, I don’t do it to make money, so I haven’t streamlined the process. For someone with experience, this process takes less time to do than it took me to describe it and format the bullet list.

(This, incidently, is one of the weakest reasons why DRM (Digital Rights Management) on ebooks is futile, rank stupidity, and an utter waste of time and money.)

So let’s say I’ve done all this.4 Let’s forget about best-sellers for a second and say I’ve done this with one of the several hard copies I own of one of my favorite books that’s currently unavailable electronically: The Well-Favored Man, by Elizabeth Willey.5

Let’s say that you read about this book and you’d like to get a copy. Hard copies are in vanishingly short supply and ebook versions aren’t available via normal channels. Just for the hell of it, you do a Google search for “Willey torrent well-favored”6 and lo and behold, you see that such a thing exists.

Do you download it?

The file might carry viruses. It might be incomplete. It might be a copy of the Spanish edition. It might be barely legible. It might, in fact, be all of those things, but there is one thing it most definitely is.

It is the only option available. Of course you download it.

Now, you’re probably like me: you’d like to give some money to the author. Maybe you’d even like to give some money to the publisher — I can’t think of good reason not to, really — but the option isn’t there, so you don’t. I mean, it’s not your goddamn fault, is it? If they wanted money, they’d have made the thing available via legitimate channels, and you’d have bought it there.

Because, seriously, it’s not about the money, is it? You’re not breaking the law to get this book because of the price tag. Given the choice between a potentially virii-laden, potentially ugly, potentially incomplete, potentially foreign-language edition copy from a torrent site and one from Amazon, I know that I would pony up and buy from Amazon. Or the publisher’s website. Or the author’s website. Or whatever. It’s safer, it’s better, and it’s just generally nicer.

But I don’t have that choice in this situation.7

Now, let’s take a look at a Shiny New Best Seller.

As we did previously, let’s create an example that flies very far from reality, so that I can’t be accused of actually doing this stuff. Unfortunately, Simon and Schuster actually publish writers I enjoy, like Stephen King. I need an example that I would never in a million fucking years ever want to read. Maybe Hachette…

Oh look: Hachette publishes Stephanie Meyer. Bingo.

So let’s say that Stephanie Meyer is publishing a new book. Perhaps something aimed at the adult readers market — some kind of modern-day horror story about how almost everyone in the world has been taken over and brain-washed by aliens and only the main character and the rest of the holy chosen who coincidentally reside in Utah and a few others have been able to resist this soul-destroying effect.8

Let’s say, for the sake of argument, that I really want to read this book. A lot. I’m salivating at the very thought of it.

Let’s also say that, for whatever reason, the hardback copy is a non-starter for me. Doesn’t matter why, but the point is: I want an electronic copy.

The book comes out in hardback. There is no electronic copy available.

What am I going to do?

Of course I am. You know I am.

Why? Because there is no legitimate copy available.

Why? Because the publisher made sure that was the case. They purposely created a situation that, in the case of The Well-Favored Man, exists only because of true scarcity and a book that never existed electronically in the first place. This other scarcity, the one I’m experiencing now, from this (no doubt) best seller, is artificial; created by the simple fact that someone at Hachette chose not to click on the ten or so buttons that need to be clicked to publish a book electronically.

Now, some folks are comparing this to the staged release of hard copies of books. “First there are hard copies,” they say. “Then there are trade paperbacks, then Mass Market paperbacks. That’s the Natural Order of Things — we’re just inserting Ebooks into the Natural Order.” Those people are not thinking; they are not taking into account that what we are talking about here is digital.

Because, you see, digital is not the same thing. It is a new animal, one of which the publishing industry is, by and large, abjectly terrified. If I want a paperback copy of a hardback that just came out, I am just plain out of luck; such a thing does not exist, and it shall not exist until the publisher makes it so.

The ebook already exists.

An hour after this hypothetical Meyers book hits the stands, someone has scanned it and put it online. It will exist on 24 thousand peer-to-peer machines in half as many hours. Or maybe someone at the publisher ‘leaked’ the electronic proofs for a little private Holiday Bonus. Or any one of a dozen other things happened.

DRM is a joke that people in the industry just don’t seem to get. There is only one way to deal with ebook piracy, and that’s by providing a safe, clean, legitimate, keeping-my-karma-shiny electronic version of the book — a clearly superior competition. That strategy actually makes piracy non-viable as a practice, let alone a consumer choice.

The publishers (and the authors) are worried about the downward trend in ebook pricing. “We won’t get paid as much,” they say. “Shouldn’t we be worried about that?”

Consider this: you can get paid marginally less, or you can get paid nothing at all.

Simon & Schuster publish Stephen King, who recently released Under the Dome. S&S released the ebook and hardback on the same day. King will no doubt release another book in 2010, and for that future release S&S will delay the ebook availability by four months.

You want to see a fun chart?

In eighteen months, look back and chart the ebook sales from the first four months of Under the Dome (following the first date-of-release for the hardback), and compare those numbers to the ebook sales from King’s next book for the first four months following the first date-of-release for that hardback. I’ll help you out: the four monthly totals for the new book will be zero.

Then: listen to the wailing from S&S (and maybe King, though I hope to god he’s smarter than that) about how ebook piracy is cutting into their sales.

This decision, which I fully believe is grounded in nothing less than a toddler-like desire to cling to the once-profitable but entirely outdated publishing structures of the past, actually creates an environment where, from a ebook-pirate’s perspective, it is a good idea to steal from them, because there is no legitimate competition in that space.

Since this mistake so closely echoes mistakes made in the music industry about 15 years ago, I have no doubt that their next epic cock-up will be to roll their ‘losses’ down to the artists on whose work they float in a sea of black ink.

The publishers are afraid of the way the world is changing. The authors are ignorant of the larger sea-changes coming in (most of them, and god love ’em for being so fixated on the writing that they are). The publishers act out of that fear, creating a situation where getting a pirated copy of the book is the only option.

And the authors end up paying for that mistake.

That’s why I’m angry.

Stuff that didn’t fit anywhere, even in the footnotes

I hope to christ that anything I create is pirated across every fucking p2p network in the world. As a relatively unknown author, obscurity is far more deadly than piracy. In the end, I will profit from more people reading one of my stories, even if I didn’t get paid for it that first time. I’m not some hippie content-wants-to-be-free guy, but I do very firmly believe in removing any and all obstacles between someone who wants to read my stuff and… my stuff.

Some folks asked me yesterday what I thought of James McQuivey’s idea to delay the ebook four months, but also give it away as a free thing with every purchase of a hardback edition. I think it’s a great idea. I thought it was a great idea when I suggested it to my agent about six months ago on Twitter. However, I won’t take credit for it – the indie gaming industry has been doing that for years; as a smaller, more nimble publishing organism, it has already felt and adapted to the changes of the digital age, and could teach the ‘real’ publishing world a thing or two about what works and what doesn’t.9

Authors: your story – the story itself – is not worth 25 bucks per copy, simply because the hardback gets priced at that amount. It’s not even worth the $7.99 for which the mass market paperback sells. Both of those amounts encompass a lot of publishing costs that having nothing to do with you or the story. The value of the story (to the publisher) is exactly however many pennies on the dollar you get paid, per copy. If you want to fight for something, fight to make sure that value does not decrease (or better yet, increases), regardless of whatever happens to the price of the books or ebooks. You have that kind of leverage, because your story is the heart of the thing in the end.

The true value of the story is in how well it connects you with your readers, both now and for years to come.

1 – I still think that’s fucking highway robbery, but that’s a rant for another day.

2 – For “sell”, read: “Rent”. Again, a rant for another day.

3 – Only the same hemisphere, though. Not within contemptuous spitting distance or anything; let’s not go crazy.

4 – I haven’t.

5 – Again, I haven’t, although if you are reading this, Ms. Willey, I would very much like to work with you to make your work available to readers again, legally. Please contact me.

6 – Or you engage in any one of a dozen other searches that yield such results. Whatever. I’m not that experienced at this stuff, which should tell you something about what the experienced people can accomplish.

7 – Maybe I’ll go buy a copy of Well-favored Man from a amazon-vetted bookseller to assuage my guilt, but that’s a pretty fucking empty gesture — it’s a reseller: the author’s not getting any of that money anyway.

8 – Not that she is.

9 – Again, a post for another day.

And by “novel”, I mean to say “utterly stupid and short-sighted.”

And by “novel”, I mean to say “utterly stupid and short-sighted.”

Earlier this evening RPGNow, Paizo, and DriveThruRPG pulled all of their Wizards of the Coast PDF products (where both new and much much much older products were available) at WotC’s request. The ability to purchase them ended at noon – the ability to download products that you’ve already bought ended at midnight.

According to Wizards of the Coast, this was done to prevent piracy. (In a followup statement, they clarified that they believe this… because they are luddite morons.)

“We have [taken these actions] to stop the illegal activities […], and to deter future unauthorized and unlawful file-sharing.”

I love the vast understatement from one gaming site today:

“I predict an increase in piracy of Wizards products.”

REALLY?

Let me take this one step further. I guarantee – not ‘predict’, but guaran-goddamn-tee that every single PDF of WotC products made available after midnight tonight will be a pirated copy.

Just… think about it for a second; you’ll see exactly what I mean.

See… before today? Sure, some people were sharing PDFs like that on file-sharing sites, and there was pirating going on. Sure, yes.

Was it because the PDFs were made available by WotC and sold online?

No. You’ve been able to get PDFs of ANY game book — hell, any book at all — even ones that have never had electronic versions available, ever since scanner technology became remotely mainstream (early 90s), because people have time, and geeks have desire for the electronic versions.

Until today, at least most of the people who wanted electronic versions of their game book were getting the PDFs the easy way: google search, got to RPGNow, click, click, download. No torrent software. No worrying if you picked up a virus with your latest PDF. Easy.

Now, the only way to get the electronic version of a WotC product is to get it from a pirate site.

I can either not get it at all (sucks for me, and WotC gets no money), or I get it from a torrent site (hassle for me, and WotC gets no money).

The pirating people? This has no fucking affect on them what. so. ever.

Well, no; that’s not entirely true.

This move by WotC, ostensibly meant to fight piracy, will actually ensure that more people will come to their site to download ALL the PDFs they want (for games, for novels… whatever — I mean, as long as they’re THERE for the DnD stuff, they might as well look around and see what else is out there, right?…).

It’s not just stupid and short-sighted. It doesn’t just ensure the piracy of their work by 100% of those that want PDFs of DnD material; it actually hurts all the other companies in the industry as well.

Before I get into this, I need to lay out a couple concepts that I’m referencing here.

Concept One: The Long Tail

“The Long Tail” describes the “niche” strategy of businesses like Amazon.com or Netflix which can be expressed – in my own words – as “sell many different products, in relatively small quantity, per product”. This is different from traditional business models, where the basic idea is “sell a large quantity of only a few things.” Traditional publishing is built on – no surprise – a traditional model; so much so that only 5% of all published authors account for 95% of the profit in publishing today.

“The Long Tail” describes the “niche” strategy of businesses like Amazon.com or Netflix which can be expressed – in my own words – as “sell many different products, in relatively small quantity, per product”. This is different from traditional business models, where the basic idea is “sell a large quantity of only a few things.” Traditional publishing is built on – no surprise – a traditional model; so much so that only 5% of all published authors account for 95% of the profit in publishing today.

Conversely, the way companies like Amazon and Netflix work allows them to profit by selling small volumes of ‘niche’ items across a broad customer base, instead of only selling large volumes of a few popular items. The group within that broad customer base that purchases a large number of “non-hit” items is the demographic that is also sometimes called the Long Tail.

This model acknowledges that the upper 20% of items listed for sale will account for most of the sales, but without negligible stocking and distribution costs, the other 80% of available products will still be profitable per unit sold and will, as a group, outsell that top 20%.

The main benefit to consumers is vastly increased product variety.

The main benefit to the distributor is that they can keep a much bigger ‘inventory’ of products in a particular niche, since warehousing isn’t such an issue, letting them outperform traditional competitors (example: Netflix can supply many titles that Blockbuster simply doesn’t offer in-store, because said title is not *already* popular).

The main (two) benefits to the independent author are:

That new method of marketing is Concept Two.

Concept Two: First, Ten

Seth Godin came up with this name and this concept, but in his own words “Three years from now, this advice will be so common as to be boring.”

Seth Godin came up with this name and this concept, but in his own words “Three years from now, this advice will be so common as to be boring.”

The basic idea is this:

Find ten people who trust you/respect you/need you/listen to you…

Those ten people need what you have to sell, or want it. And if they love it, you win. If they love it, they’ll each find you ten more people (or a hundred or a thousand or, perhaps, just three). Repeat.

If they don’t love it, you need a new product. Start over.

As he points out, this approach changes everything, as compared to typical publishing. You don’t market to the anonymous masses. They’re not anonymous and they’re not masses. You market to people who are willing participants. The idea of a ‘launch’ and press releases and the big unveiling is a bad one. Instead, a gradual build turns into a swell turns into a wave.

(Seth is very smart – damn sight smarter than me. You should be reading his blog.)

So the basic idea is that (a) you have this Long Tail demographic you can market to, and you have the time to do so, because you don’t have to worry about running out of time and getting your book backlisted/discontinued — that’s just not an real concern anymore. You just need to Find Ten, over and over again. This includes things like:

Look at those three things: anything there strike you as something a publisher can do better than the author, plus perhaps their first “Ten” people?

((To be fair, there’s no reason at all this doesn’t apply to an author working in Traditional publishing as well. In that case, you want/need your Agent and Publishing Editor to be two of your First Ten, so that they can evangelize within the existing Trad Publishing networks that you-the-author could never reach. That’s obviously valuable, if the option is available to you.))

Now, ponder this: all this marketing theory stuff is not hypothetical. This is something already happening today in one of the publishing niches that has raced ahead of the mainstream publishing genres (fiction, non-fiction) by virtue of never having been part of mainstream publishing in the first place.

I’m speaking of roleplaying game publishing (which you might have guessed from the title of the post). Lemme ‘splain.

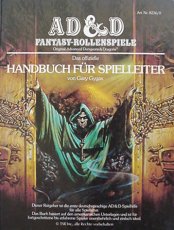

Back in the late 70s and early 80s, roleplaying games were on their first upswing and, since the primary product of the roleplaying gaming industry at the time was books, game developers looked, naturally, to the publishing industry for ideas on how to MAKE books – how to publish.

Back in the late 70s and early 80s, roleplaying games were on their first upswing and, since the primary product of the roleplaying gaming industry at the time was books, game developers looked, naturally, to the publishing industry for ideas on how to MAKE books – how to publish.

And let me tell you, those were some meticulous, geeky bastards back in the day; they figured out how publishing worked and in most cases they followed the traditional publishing model to the letter. Also, they usually aimed for the highest quality products they could (or, often, couldn’t) afford to produce. You should SEE some of the books they turned out – big, beautiful, heavily illustrated, hardbound, double-stitched – you could kill a caribou with the first (or second) edition of Advanced Dungeons and Dragons – don’t even get me started on the original Champions rulebook.

There was, of course, a problem. Roleplaying games are a niche market. Super-niche. The nicheiest. You could have one, probably two, MAYBE three or four product lines successfully pushed into this niche market using traditional publishing methods (each additional line taking a bite out of the success of the other lines) before the niche was full and anything that came after failed. Perhaps not right away, but they’d fail.

TSR (publishers of DnD) was even bought out, and all the others? There is one handful of gaming companies (full-time employing a double handful of people) that have survived from then to now. Meanwhile, the list of those that went under, trying to publish using traditional means, would fill a phone book.

Most people gave it up.

Then came the internet.

With the internet came mailing lists, usenet, and (eventually) forums that in some cases became places of collaboration and creation for that niche market. Some of the early products of that time (FUDGE, to name one) are still popular today, but the basic idea here is that this experience informed some game designers that their ideas had merit, and even an audience.

They just didn’t have any idea how to turn that idea into a PRODUCT without bankrupting themselves. First, the book publishing cost was prohibitive and Second: even if they found an affordable way to publish, how do you get your niche-within-a-niche idea out to the right people?

Then came Dungeons and Dragons 3rd edition, which did a remarkable thing by releasing their rules set as Open Source, basically allowing anyone legal permission to write adventures and source material for the game, and publish it however they like, with one simple caveat: “write it in such a way that the customer still needs our main rulebooks to play.”

Suddenly, the problem with “How do you get your work to the right audience” was gone (provided you wrote stuff for DnD – the biggest product line within Gaming, so not much of a hardship), which left hundreds of creators with only one problem to solve: how to get our work out to people without bankrupting ourselves.

More importantly, this was a group of people who never really associated themselves (mentally) with traditional publishing – they’re gamers, man – so there’s no stigma to the idea of self-publishing. Quite the contrary: in that niche market, self-publishing was the DREAM – a mix of “rock and roll” and “my god, I might actually make some money off this hobby I love!”

Now these were geeky, meticulous bastards (notice a theme?), and when faced with a problem like that, they worked the HELL out of it. By a glorious bit of serendipity, available technology on the internet was finally catching up to their needs at almost the same time: relatively affordable and good-quality print-on-demand, secure and user-friendly online ‘storefront’ software that let you sell electronic files easily. FREE services for acquiring legitimate ISBN numbers and getting listed on sites like Amazon, so that your new DnD module would show up in Amazon searches alongside products from the “big boys.”

Heady times.

When the wave of 3rd edition DnD publishing waned, what was left behind was all that knowledge, experience, creative forums, and the services to make publishing your own stuff possible.

Which is exactly what people did. Today, there are HUNDREDS of products available to this roleplaying gaming niche, and no one ‘going out of business’. Sure, some stuff never sells (because it’s crap), but the good stuff rises – slowly, most of the time – to the top, and finds its target audience, who evangelize and market for those games without much help from the original creator at all, aside from their participation in the social networks surrounding that niche market.

Which is exactly what people did. Today, there are HUNDREDS of products available to this roleplaying gaming niche, and no one ‘going out of business’. Sure, some stuff never sells (because it’s crap), but the good stuff rises – slowly, most of the time – to the top, and finds its target audience, who evangelize and market for those games without much help from the original creator at all, aside from their participation in the social networks surrounding that niche market.

Most of their sales come from:

Sound familiar?

Sounds like a real-world example of what people are theorizing indie publishing will look like.

Here’s the thing: indie publishing ALREADY works like the ‘theory’ posits: it’s just that only a small group has realized it so far.

I’m being interviewed by another writing site in a few days (this one live, via Skype, with someone in Austrailia – it’s is SO COOL to live in the future), and they were kind enough to send me some of the questions they planned to ask, so I could get my thoughts in order. (Good plan, on their part.)

The last question on the list is a doozy: “Why are you still pursuing traditional publishing for Hidden Things when there are so many other options out there today?”

I’ll be biting my tongue not to say “masochism”.

But there’s a flipside to that question, and it goes something like this: “You have a book that was good enough to get representation from an agent, and which you’re (slowly) bringing in line with a publisher’s desires and looking at some success with actually getting the thing published in the traditional market – getting over the threshold, really. Why are you putting so much time into learning about indie publishing?”

Like the header warns at the top of the page, I’m all about my perpetual projects and daily obsessions. The possibilities that exist out there for authors regardless of how they want to get their work out to a reader are definitely one of my obsessions, and as such, it’s one of those things that will continue to get a lot of posting love from me on this blog. Hopefully it’s not boring folks too much; me, I find it fascinating.

I’ve made a living of walking into completely unfamiliar new businesses every couple years, learning said business, then teaching those in the business about how to do it better — that’s how I pay the bills. One of the things I do in those situations is question the standard operating procedures. “It’s done this way because that’s how we do it” is an immediate red flag to me, and the more I learn about how publishing functions today, the more red-flags I see.

In the movie and music industry, the big companies started to focus only on big-money-making projects, and as a result artists that wanted to… you know… do art (or at least their own thing) went independent. The same focus on big-money-makers has been happening within the publishing industry (thanks in part to consolidation of publishing into a half-dozen meta-imprints), but there hasn’t been the same leap to indie publishing. Affordable tools are out there, the quality-in-production is there; authors have the ability to publish, distribute and market books without any involvement from mainstream publishers, thanks to print on demand (POD), e-book technologies, Web 2.0 and the fact that Amazon is now the #2 bookseller in North America and #1 worldwide — but the authors don’t move, because of the stigma of self-publishing.

Yes, before house-consolidations began, publishers were everywhere and there was truth to the idea that an other only self-published if they weren’t good enough to make it ‘legitimately’. This is no longer true, but the characterization of self-published authors as talentless hacks persists.

“It’s that way because it’s always been that way.”

That’s not survival behavior. It’s not even intelligent behavior, which is puzzling, because it’s coming from intelligent people.

I post a lot on this topic right now because I’m trying to figure it out.

Caveat lector.