My chat pinged.

Them: Hey.

Me: Yo.

Them: I would REALLY like it if you weighed in on the thing in the forum.

Me: The what-now?

Them: On the forum. Someone linked an op-ed piece and it turned into a “big five bash” by people who would dance a jig if they got picked up. Your perspective might help.

As a frequent victim of what I now call Rule 386, I was wary. There’s not much use (and a great deal of time lost) in my getting embroiled in some internet debate on the goods and bads of the publishing world.

Still, it was a request from a friend, so in I went.

Luckily, the discussion wasn’t as bad as I’d expected, but I did spot a number of the familiar themes.

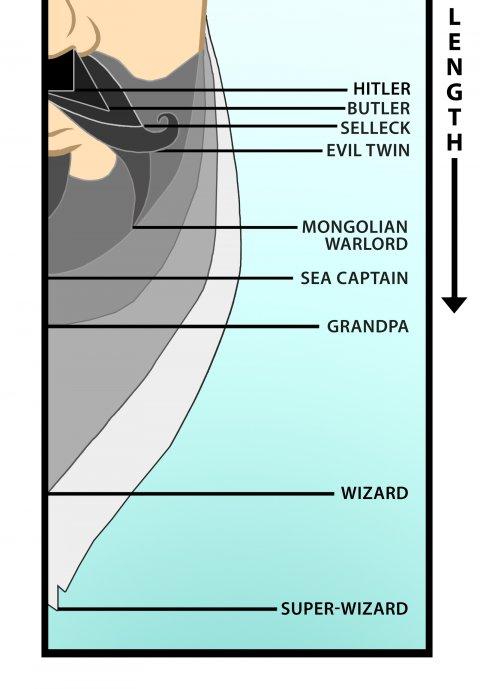

So many gatekeepers are wearing “the next Hunger Games” glasses.

That phrase really worked better a few years ago when it was Harry Potter glasses.

Because he wore glasses. Nevermind.

The Enormous Five aren’t just looking for the next best-seller. They decide — before seeing it — what the next best-seller will look like, meaning a narrower and narrower idea of what they they’ll publish. Standard megastar bestseller mindset.

It’s not enough to call them the Big Five, anymore, I guess. They don’t seem monolithic and inhuman enough?

Reversion of rights to the author is a joke in most contracts now.

I’ve actually got a funny/awesome story to tell about that, but I’m going to save it for next week.

Writers should just publish their own work and let people decide.

Which, though the original poster might not have intended it, implies quite strongly the editors and agents within publishing houses or literary agencies are not people.

Really, I think that’s what a lot of those quotes are saying, and that puts me in mind of one final quote:

Mechanistic dehumanization occurs when features of human nature (cognitive flexibility, warmth, agency) are denied to the subject. Targets of mechanistic dehumanization are seen as cold, rigid, lacking agency, and likened to machines or objects. Mechanistic dehumanization is usually employed on an interpersonal basis (e.g. when a person is seen as a means to another’s end).

That’s what I want to talk about.

As a writer, I’m in an unusual situation, and I have been for quite a long time. I’m blessed to know quite a few people (there’s that word again) in traditional publishing — published writers, editors, and of course agents. I have some experience with what it’s like to be on the “creator” side of things, and at the same time I get a fly-on-the wall view of what it’s like for those ‘in the industry’ — I’ve even written about it. Sharing my life with Kate has given me the ability to speak frankly and (often) sanely with my own agent and editor.

Now, I have my own problems with traditional publishing. They are well-documented.

But I don’t have a problem with the people in publishing. I disagree with those who imply that agents and editors are just looking for the next Lemony Hunger Potter, because I’ve seen those editors and agents fight for books they believe in.

Like mine, for one easy example. Hidden Things, for all that it may be beloved by tens of dozens of people, walked a long road to publication. My agent worked with me through a complete edit before we signed a contract, and my HarperCollins editor did the same (again, before we had a contract). That’s significant.

You know what ‘before we had a contract’ means, really?

It means ‘before there was even the slightest chance they would get paid for their time.’

All that work was to get the book to the point where it would pass muster with the other parts of the agency and/or publishing house.

Some might wonder why they do that, but I live with an agent, so I’ve already figured out the answer.

Love.

Once upon a time, Kate worked in New York; part of the second largest literary agency in the city (so large and well-recognized that — to this day — they still don’t bother with a web site). She worked her way up, sacrificing so that she could live and work at the heart of publishing.

She for damn sure wasn’t doing it for the money — Manhattan isn’t cheap, and working past six every day, hauling twenty pounds of manuscripts home every weekend (to read on her own time), and pulling down ‘specialist’ wages left her about enough for a rich assortment of ramen noodle flavors.

That went on for over a decade.

Five years ago, this very day, Kate and I got married. Our anniversary is, very nearly, also the anniversary of her own agency. In those five years Kate has (at my conservative estimate) read approximately three hundred twenty thousand pages of queries, partials, and manuscripts. That’s three full-length young adult novels a week for half a decade, and doesn’t include reading work from her signed authors, dealing with contracts, handling perpetually late payments, and all the rest.

She shows no sign of slowing down.

Further, as much as I love my wife (and count myself so very, very lucky), I know this: my agent does the same thing. My editor does the same thing. Your agent and editor (even the one you haven’t found yet) does the same thing.

There is only one reason someone would do that, and it’s not to find the next the next commercial hit.

It is, simply, love of a good story, to a degree that would shame most of us.

I hate the phrase “gate keeper” applied to agents and editors. It turns these people — these very human, motivated, story-loving people — into some kind of minor boss you have to fight to get to the next level of a video game.

They aren’t.

They are, in fact, the allies you recruit to ensure victory. Anyone with any sense should count themselves lucky to have them.

Yes, agents must be particular about what work they represent. Sturgeon’s Law applies.

Yes, editors must be particular about what work they will take on, and must justify that work to marketing, payroll, et cetera, ad nauseum.

Yes, these people (again, people) must judge, and sometimes the judgement doesn’t go your way, and that sucks.

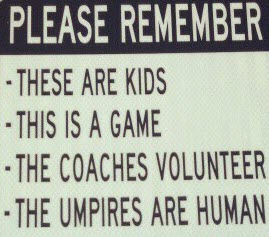

But the Umpires are Human.

Today, remember that. If you have the means or the desire, say thanks. Do it for me.

Call it an anniversary gift.