[[Sometimes, I find myself writing full-on academic papers on literary stuff. Sometimes (even more rarely) I feel inclined to share them. This is one of those times. – Doyce]]

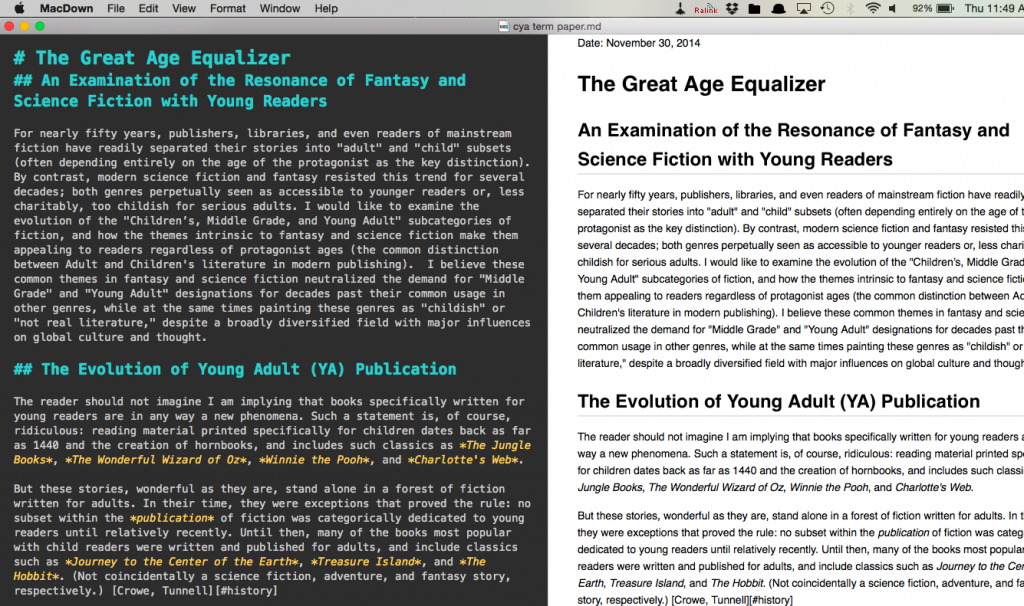

For nearly fifty years, publishers, libraries, and even readers of mainstream fiction have readily separated their stories into “adult” and “child” subsets (often depending entirely on the age of the protagonist as the key distinction). By contrast, modern science fiction and fantasy resisted this trend for several decades; both genres perpetually seen as accessible to younger readers or, less charitably, too childish for serious adults. I would like to examine the evolution of the “Middle Grade and Young Adult” subcategories of fiction, and how the themes intrinsic to fantasy and science fiction strongly parallel those of mainstream middle-grade and young adult, thus appealing to readers of all ages. I believe these common themes in fantasy and science fiction neutralized the demand for “Middle Grade” and “Young Adult” designations for decades past their common usage in other genres, while at the same times painting these genres as “childish” or “not real literature,” despite a broadly diversified field with major influences on global culture and thought.

The Evolution of Adolescent Publication

The reader should not imagine I am implying that books specifically written for young readers are in any way a new phenomena. Such a statement is, of course, ridiculous: reading material printed specifically for children dates back as far as 1440 and the creation of hornbooks, and includes such classics as The Jungle Books, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Winnie the Pooh, and Charlotte’s Web.

But these stories, wonderful as they are, stand alone in a forest of fiction written for adults. In their time, they were exceptions that proved the rule: no subset within the publication of fiction was categorically dedicated to young readers until relatively recently. Until then, many of the books most popular with child readers were written and published for adults, and include classics such as Journey to the Center of the Earth, Treasure Island, and The Hobbit. (Not coincidentally a science fiction, adventure, and fantasy story, respectively.) [Crowe, Tunnell][#history]

It wasn’t until the publication of The Outsiders in 1967 that a formal definition of young adult literature began to emerge. What separated S. E. Hinton’s story from the books people in this age range read prior to that point was simple: it was a book about young adults and written for young adults. Previously (and even contemporaneously, as with The Chosen, also published in 1967) books with young adult characters were not written for that age group [Wells][#wells].

This change was both a good and bad thing: good in that it began the shift in perception that would lead publishers to treat non-adult fiction as a special and noteworthy thing, bad in that the strong initial influence of The Outsiders and the simplistic criteria of “written about kids, for kids” led to a general guideline for identifying children’s, middle-grade, and young adult fiction based solely on the age of the protagonist, and ignoring any other factors that might be as important, or even vastly more important.

This isn’t to say The Outsiders flipped a switch and publishing suddenly perceived a new category of fiction: it took several decades for this subset of literature to reach the point where the work being put out by publishers consistently satisfied its intended audience. In mainstream Young Adult fiction, the 1970s were overwhelmed with “single problem novels”, dealing with problems young adults faced, but often in an unsatisfactory or simplistic way. The 1980s saw a boom in romance and horror fiction, but it wasn’t until the 1990s and the rise in “middle grade” literature, which expanded the publishers’ perceived audience, that YA authors were free to tackle more serious subjects and to introduce more complex characters and considerations of ambiguity. [Cart][#cart].

The Long Battles within Fantasy and Science Fiction

The genres of fantasy and science fiction had no similar watershed moment, triggered by the release of an “Elves versus Dwarves” version of The Outsiders. Luminaries in the field continued to write what they had always written, and paid no particular attention to the intended reader’s age, though they suffered no lack of popularity with young readers: Ursula Le Guin’s Left Hand of Darkness, which was published only two years after Hinton’s classic, won the Hugo and Nebula in 1970, and remains popular with readers of all ages; Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game, published in 1977 (when mainstream young adult fiction struggled with mediocre “problem novels”) features a young boy in a military organization and explored themes that simultaneously appealed to young readers and even today make it suggested reading for many military organizations, including the United States Marine Corps. [USMC][#marines]

Lacking an “Outsiders moment,” these genres were able to produce stories free from strict categorization of adult versus non-adult, which allowed each story to find its best audience on its own merits.

Rather than needing to age-market their books, writers of science fiction and fantasy instead struggled with the perception that all of their work was unsuitable both for children and adult readers: in the first case, too dark or dangerous for the young…

… one friend of mine said, “I’ll tell you something fantastic. Ten yeas ago (1964), I went to the children’s room of the library of such-and-such a city, and asked for The Hobbit; and the librarian told me, ‘Oh, we keep that only in the adult collection; we don’t feel that escapism is good for children.'” [Le Guin, Dragons][#lgd]

… while too whimsical for adults.

“A great many Americans are not only antifantasy, but altogether antifiction. We tend, as a people, to look upon all works of the imagination either as suspect, or as contemptible.” [Le Guin, Dragons][#lgd]

This paradox has plagued science fiction and fantasy writers for decades – critics dismiss the genres as vapid or trite, while at the same time denouncing them for the potential harm they can bring to impressionable younger readers introduced to serious topics before they are ready. It is not a recent development: Baum argued for the importance of imagination and the fantastic in the first introduction to The Wonderful Wizard of Oz in 1900, and Tolkien addressed the question in his essay “On Fairy Stories” decades before Le Guin wryly argued the critics were correct, but confused: the stories were both whimsical and dark, in exactly the way that made them perfect for both adults and children.

“Fantasy is the great age equalizer; if it’s good when you’re 12 it’s quite likely to be just as good, or better, when you’re 36.” [Le Guin, Dreams][#lgdr]

No Such Thing as Coincidence

It’s difficult if not impossible for any reader familiar with contemporary publishing to miss the fact these arguments (and criticisms) are remarkably similar to those leveled at Middle Grade and Young Adult writers and books today [Monseau][#monseau]. In almost every case, the top modern YA authors face marginalization and outright dismissal from “serious” critics for the same reasons (inappropriate themes, or jejune writing – the critics still can’t seem to decide [Gurdon][#wsg]), and have found themselves forced to justify their own work in the court of public opinion [Johnson][#yasaves] [Drew][#drewpop], as in this passage by Shedrick Pittman-Hasset, which could just as easily have been written by Ursula Le Guin in the mid-1970s.

The darkness exists. Always has and, [insert appropriate deity here] help us, always will. That we are now able to speak of it in the presence of those that have actually, or could actually experience it is a Good Thing. For those that have spent time in the dark places, these books demonstrate they are not alone; that with strength and perseverance, they can emerge and be free. Those that have not walked that dark path gain a degree of perspective on their own problems and also move away from the “blame the victim” mentality that often goes hand-in-hand with silence. As one fellow author brilliantly put it “We need to see someone be strong when they face their demons, so we can be strong when we do.” [Pittman-Hasset][#ph]

These commonalities between modern YA, and speculative fiction going back over a century point to clues that reveal the reason why science fiction, fantasy, and mainstream middle-grade and young adult publishing all produce stories popular with adolescents, while at the same time attracting both the scorn and censure of so-called serious critics.

The Elements of Adolescence

Adolescence can be characterized by a few key themes. Gisela Konopka of the Center for Youth Development and Research at the University of Minnesota developed a statement on the concept of normal adolescence in 1973. Out of her research with young adults, five key concepts emerged: an “experience of physical sexual maturity,” an “experience of withdrawal of and from adult benevolent protection,” a “consciousness of self in interaction,” a “re-evaluation of values,” and “exploration and experimentation” [Konopka, 298-300][#kono].

Examining these five elements as they relate to adolescent and adult fiction is enlightening.

Sexual Maturity

It’s not difficult to see the draw of this topic in fiction; “sex sells” has become more of a punchline than a guideline, but in the realm of adolescent fiction, the approach is more nuanced, and may often be one of the primary themes of the story, explored with care and consideration (rather than a way to spice up up chapter three).

“Can I hug you?”

“Do you want to?” said Bod.

“Yes.”

“Well then.” He thought for a moment. “I don’t mind if you do.” [Gaiman, 254][#ggyb]

It’s obviously no more difficult to find examples of protagonists exploring sexual maturity in science fiction and fantasy; the surprising thing is that the topic is often handled with just as much consideration, if not in fact a sort of circumspect care.

“Then, Eowyn of Rohan, I say to you that you are beautiful. In the valleys of our hills there are flowers fair and bright, and maidens fairer still; but neither flower nor lady have I seen till now in Gondor so lovely, and so sorrowful. It may be that only a few days are left ere darkness falls upon our world, and when it comes I hope to face it steadily; but it would ease my heart, if while the sun yet shines, I could see you still.” [Tolkien, RoK, 238][#tolkienrok]

Withdrawal from Adult Protection

This theme is one we have revisited often in our study of Newbery award winning books. It is, if not ubiquitous in adolescent fiction, nearly so. Poor Meg in Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time must step away from the safety of adult protection no fewer than five times in a single story, leaving behind her mother, Mrs. Who, Aunt Beast, her father and, finally, rejecting the ultimate all-encompassing adult protection personified by IT [L’Engle][#wrinkle].

Among science fiction and fantasy ostensibly written for adults, perhaps one of the most definitive stories of the withdrawal from adult protection comes to us via the classic Ender’s Game, in which Ender Wiggin is not only taken from his family and forced through a constantly escalating spiral of adult responsibilities, but ultimately reverses the adult-child protection dynamic by saving all of humankind (and sacrificing his childhood in the process) [Card][#enders].

Consciousness of Self

This concept might be difficult to define or to identify examples, were it not such a critical element in young adult fiction. The realization that you are an individual being – someone and something separate from your family and friends – is a lightning strike of awareness, and any story that truly represents adolescence will encounter it.

Aaron Starmer’s The Riverman essentially opens the book with Alistair’s moment of clarity and consciousness, bought with the life of a boy named Luke Drake, when Alistair was only three years old.

The memory of Luke may very well be my first memory. Still, it’s not like those soft and malleable recollections we all have from our early years. It’s solid. I believe in it, as much as I believe in my memory of a few minutes ago. [Starmer, 6][#starmer]

It’s fair to say that the exploration of consciousness of self is one of the core callings in science fiction; it is hardly difficult to find examples of this exploration in the genre, especially in the classics of the early twentieth century, such as Asimov’s Robot series. But within my personal timeline, the definitive example is a short story by Robert Heinlein entitled Jerry Was a Man[Heinlein][#heinlein], in which the question of the sentience and free will of a genetically modified chimpanzee is decided in a court of law. In many ways, it set the bar for the search for the meaning of consciousness in a genre uniquely equipped for the task.

Re-evaluation of Values

To be completely honest, searching for this element of adolescence in fiction, while certainly important, is almost cheating: every expert on the structure of story can agree (where they agree on little else) that the protagonist’s re-evaluation of values is an intrinsic part of the conclusion of a story. It can be a private thing, as with Miranda slowly letting her relationship with Sal change in When You Reach Me, or powerfully defiant in Jacqueline Woodson’s Brown Girl Dreaming, “the revolution”.

I want to write this down, that the revolution is like

a merry-go-round, history always being made

somewhere. And maybe for a short time,

we are a part of that history. And then the ride stops

and our turn is over.

We walk slow toward the park where I can already see

the big swings, empty and waiting for me.

And after I write it down maybe I’ll end it this way:

My name is Jacqueline Woodson

and I am ready for the ride. [Woodson][#woodson]

Among the genres of fantasy and science fiction, these moments are no less important, and form some of the most memorable scenes in our favorite books, as in this conclusion to Ready Player One.

“I’ve really missed you, you know that?”

My heart felt like it was on fire. It took a moment to work up my courage; then I reached out and took her hand. We sat there a while, holding hands, reveling in the strange new sensation of actually touching one another.

Sometime later, she leaned over and kissed me. It felt just like all those songs and poems had promised it would. It felt wonderful. Like being struck by lightning.

It occurred to me then that for the first time in as long as I could remember, I had absolutely no desire to log back into the OASIS. [Cline][#cline]

Exploration and Experimentation

As with the withdrawal from adult protection, this element is almost ubiquitous in adolescent fiction. From camping out in a museum in The Mixed-up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankenweiler to Fiona’s life in Aquavania in The Riverman to Meg learning to “tesser well” in A Wrinkle in Time.

Likewise, the genres of fantasy and science fiction seem to embody exploration and experimentation like no others, and at more levels: certainly, the protagonists of the stories embrace this idea, but at a more meta level the readers themselves are exploring – wandering the halls of Castle Amber, walking the paths of Mirkwood, sailing starry skies on Barsoom, or diving into the endless digital seas of OASIS – all worlds beyond the norm, beyond those we might find in tamer, mainstream fiction. And this says nothing about the authors of these stories: it is called speculative fiction, after all, and its creators are experimenting almost by definition.

Bringing the Five into One

In lay terms, these five elements are, of course, most easily and simply expressed as “coming of age,” perhaps the definitive theme of adolescent fiction, but also one at the core of fantasy and science fiction.

“The most childish thing about A Wizard of Earthsea, I expect, is its subject: coming-of-age. Coming-of-age is a process that took me many years; I finished it, so far as I ever well, at about age 31; and so far I really feel rather deeply about it. So do most adolescents. It’s their main occupation, in fact.” [Le Guin, Dreams][#lgdr]

Even setting Le Guin aside, it’s a simple matter to prove that science fiction and fantasy writers have always seen these elements as important to the types of stories they were writing.

Tolkien suggested that fairy stories allow the reader to review his own world from the “perspective” of a different world. This concept, which shares much in common with “consciousness of self”, “re-evaluation of values” and “exploration and experimentation”, Tolkien calls “recovery,” in the sense that one’s unquestioned assumptions might be recovered and changed by an outside perspective [Tolkien][#tolkien]. Susan Wood, in her introduction to Le Guin’s The Language of the Night, wrote at length on the “necessity for internal exploration, provided by fantasy, to produce a whole, integrated human being.” [Wood][#wood]

Let us, as a further example, consider a simple hobbit.

Bilbo Baggins arrived on the literary scene in 1937. At the outset of his tale, he leaves the safety of the only home he has ever known (the home built by his father and mother) and steps into the larger world by signing up for a mysterious undertaking with the potential for great reward and great risk. Before he can do this, however, he must (with the help of a strong nudge from an old friend) take a hard look at his life and realize that, deep in his heart, he longs for more; only then can he race out his door without his handkerchief or any other proper preparation, and into a grand adventure There and Back Again.

Put another (much more boring) way, he experiences withdrawal from benevolent protection, a consciousness of self in interaction, a re-evaluation of values, and a great deal of “exploration and experimentation.” He is, in short, coming of age, and his story continues to resonate with readers of all ages, but most especially those going through the same sort of things in their own lives – children.

At the beginning of the story, Bilbo is fifty-five years old.

By our modern standards, this could not possibly be a story meant for children, nor was it published for children at the time.

It was published for readers, and found those who needed and wanted it most.

The Critical, Yet Censured, “Kiddy Story”

Here, then, is part of the secret of a story’s appeal to young readers, and one reason why adolescent subsets of science fiction and fantasy did not gain real momentum in publishing until the late 1990s and early 2000s: these are stories that already speak to the core experiences of adolescence; that resonate with younger readers; that create an “age barrier” so permeable as to be virtually non-existent.

In the same way that speculative fiction has always attracted younger readers alongside adults, more and more young adult and middle grade stories attract adult readers alongside children. That both categories uniformly earn the scorn of serious literary critics is more a judgement on the critics, than the stories.

Conclusion

“I don’t think there is such a thing as a bad book for children. … Well-meaning adults can easily destroy a child’s love of reading. Stop them reading what they enjoy or give them worthy-but-dull books that you like – the 21st-century equivalents of Victorian ‘improving’ literature – you’ll wind up with a generation convinced that reading is uncool and, worse, unpleasant.” [Gaiman][#gaiman]

As Ursula Le Guin might say, a story doesn’t have to be about real things to be about true things. This is the secret to the all-ages appeal of science fiction and fantasy – stories for adults that appeal to children, and (in the case of these newer adolescent categories) stories for children that entice all but the most jaded adult: truth. Science fiction and fantasy always, from their very inception, focused on themes that lie at the heart of the adolescence. For this, they have have always suffered casual dismissal, and enjoyed heartfelt adoration by those readers able and willing to recognize the wonder, whimsy, and (above all) childishness of their lives.

That they now have allies and companions within the mainstream is, in the opinion of this newcomer to young adult fiction, wonderful, hopeful news.

[#cart]: Cart, Michael. “From Insider to Outsider: the Evolution of Young Adult Literature.” Voices from the Middle 9.2 (2001): 95-7.

[#cline]: Cline, Earnest. Ready Player One. Random House. 2011.

[#drewpop]: Drew, Bernard A. The 100 Most Popular Young Adult Authors: Biographical Sketches and Bibliographies. Englewood, CO: Libraries Unlimited, 1997.

[#enders]: Card, Orson Scott. Ender’s Game. Tor. 1977.

[#gaiman]: Gaiman, Neil. http://neilgaiman.com. 2003.

[#ggyb]: Gaiman, Neil. The Graveyard Book. HarperCollins. 2008.

[#heinlein]: Heinlein, Robert A.. “Jerry Was a Man”. Assignment in Eternity. Fantasy Press. 1953

[#history]: Crowe; Tunnell. A chronology of history and trends in children’s and YA literature. 2012

[#kono]: Konopka, Gisela. “Requirements for Healthy Development of Adolescent Youth.” Adolescence 4 (1973): 291-315.

[#lgd]: Le Guin, Ursula. “Why Are Americans Afraid of Dragons”. PNLA Quarterly 38, Winter 1974

[#lgdr]: Le Guin, Ursula. “Dreams Must Explain Themselves” Algol 21, Nov 1973

[#marines]: REVISION OF THE COMMANDANTS PROFESSIONAL READING LIST. 2013.

[#monseau]: Monseau, Virginia. Responding to Young Adult Literature. Boynton/Cook Publishers. 1996.

[#ph]: Pittman-Hasset, Shedrick. How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Embrace the Darkness. June 5, 2011.

[#starmer]: Starmer, Aaron. The Riverman. Farrar Straus Giroux. 2014.

[#tolkien]: Tolkien, J.R.R.. “On Fairy Stories”. Essays Presented to Charles Williams, 1947

[#tolkienrok]: Tolkien, J.R.R.. Return of the King, Houghton Mifflin. 1955.

[#wells]: Wells, April Dawn. Themes found in young adult literature, April 2003.

[#wrinkle]: L’Engle, Madeleine. A Wrinkle in Time. Macmillan. 1962.

[#wood]: Wood, Susan. “Introduction” The Language of the Night (Le Guin): 17.

[#woodson]: Woodson, Jacqueline. “the revolution”. brown girl dreaming. Penguin. 2014.

[#wsg]: Gurdon, Meghan. “Darkness Too Visible”, Wall Street Journal. June 4, 2011.

[#yasaves]: Johnson, Lucas J.W.. The YA Saves Phenomenon. June, 2011.