Habituals Update

It’s been relatively quiet around Casa Testerman for the past week or so. There was a trip to Philadelphia, thick with unexciting wardrobe malfunctions, but otherwise I’m plugging along with writing, reading, and trying to get these damn habits locked in. Lemme sum up:

Reading:

It’s been a very good month for me as far as new reading experiences go; first there was Terry Pratchett’s Nation, then Neil Gaiman’s wonderful Graveyard Book, and I had the pleasure of catching up with all the cool kids and read The Lies of Locke Lamora on the Philly trip. Great book. Just enough ‘new’ in the fantasy world, with great characterization and plotting. Capers are capered, swashes are buckled, and a great many skulls are duggeried. I came fairly close to sleeping on the couch a couple times, thanks to interrupting Kate’s own reading with chortling, out-of-context excerpts. Recommended (as are the others I mentioned – highly).

Writing:

The “Adrift” story continues, in which Finnras seems to be engaging in some kind of Cunning Plan. We’ll see if he’s as good at such things as Locke Lamora. Odds are not good.

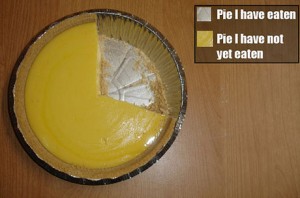

Habit the First – Tracking what I Eat

This went very well in the first week – I even dropped a few pounds. (Actually, according to the website on which I track such things, I dropped too much in one week, and now they want to me to eat more this week — as in… a lot more… “I can’t afford a whole cow!” more — it’s confusing.

Habit the Second — Getting up an Hour Earlier

This one isn’t going as well. Yes, I’m getting up earlier, but I never have to use an alarm clock normally, and I for damn sure have to right now. Also, I’m dragging through large portions of the day, short on energy and long on nap-tropism.

I think part of the problem is that I haven’t set up any kind of reward for when I succeed at this each day (the other part of the problem is that I have no personal desire or investment in this – it’s wholly external) — so I need some help with that: what kind of reward should I be giving myself for getting up at the crack of dawn every day?

Suggestions need to be something concrete: that early in the morning I don’t think highly enough of my fellow humans for “a sense of moral superiority” to mean anything. Gimme some ideas in the comments.

The New Frontier of Indie Publishing has already been Mapped Out (on a Battlemat)

Before I get into this, I need to lay out a couple concepts that I’m referencing here.

Concept One: The Long Tail

“The Long Tail” describes the “niche” strategy of businesses like Amazon.com or Netflix which can be expressed – in my own words – as “sell many different products, in relatively small quantity, per product”. This is different from traditional business models, where the basic idea is “sell a large quantity of only a few things.” Traditional publishing is built on – no surprise – a traditional model; so much so that only 5% of all published authors account for 95% of the profit in publishing today.

“The Long Tail” describes the “niche” strategy of businesses like Amazon.com or Netflix which can be expressed – in my own words – as “sell many different products, in relatively small quantity, per product”. This is different from traditional business models, where the basic idea is “sell a large quantity of only a few things.” Traditional publishing is built on – no surprise – a traditional model; so much so that only 5% of all published authors account for 95% of the profit in publishing today.

Conversely, the way companies like Amazon and Netflix work allows them to profit by selling small volumes of ‘niche’ items across a broad customer base, instead of only selling large volumes of a few popular items. The group within that broad customer base that purchases a large number of “non-hit” items is the demographic that is also sometimes called the Long Tail.

This model acknowledges that the upper 20% of items listed for sale will account for most of the sales, but without negligible stocking and distribution costs, the other 80% of available products will still be profitable per unit sold and will, as a group, outsell that top 20%.

The main benefit to consumers is vastly increased product variety.

The main benefit to the distributor is that they can keep a much bigger ‘inventory’ of products in a particular niche, since warehousing isn’t such an issue, letting them outperform traditional competitors (example: Netflix can supply many titles that Blockbuster simply doesn’t offer in-store, because said title is not *already* popular).

The main (two) benefits to the independent author are:

- Those whose products could not — for economic reasons — find a place in pre-Internet information distribution channels can realize a burst of financially successful creativity that finds its audience. One example of this is YouTube, where quality artists within any number of disciplines have found success that they would never have gotten via traditional channels.

- The new ability to maintain a large ‘niche’ inventory without warehousing overhead means that the creator has time to find their audience via a new method of marketing that has only recently become viable, let alone profitable.

That new method of marketing is Concept Two.

Concept Two: First, Ten

Seth Godin came up with this name and this concept, but in his own words “Three years from now, this advice will be so common as to be boring.”

Seth Godin came up with this name and this concept, but in his own words “Three years from now, this advice will be so common as to be boring.”

The basic idea is this:

Find ten people who trust you/respect you/need you/listen to you…

Those ten people need what you have to sell, or want it. And if they love it, you win. If they love it, they’ll each find you ten more people (or a hundred or a thousand or, perhaps, just three). Repeat.

If they don’t love it, you need a new product. Start over.

As he points out, this approach changes everything, as compared to typical publishing. You don’t market to the anonymous masses. They’re not anonymous and they’re not masses. You market to people who are willing participants. The idea of a ‘launch’ and press releases and the big unveiling is a bad one. Instead, a gradual build turns into a swell turns into a wave.

(Seth is very smart – damn sight smarter than me. You should be reading his blog.)

So the basic idea is that (a) you have this Long Tail demographic you can market to, and you have the time to do so, because you don’t have to worry about running out of time and getting your book backlisted/discontinued — that’s just not an real concern anymore. You just need to Find Ten, over and over again. This includes things like:

- New Media Marketing: building and managing a presence on social networks and online or virtual communities. This is very low-frequency, low-intensity, and cost effective.

- Buzz: Basically word of mouth, the transmission of commercial information from person to person in an online or real-world environment. There was a statistic bounced around this year’s Technology of Change conference that 85% of book sales were thanks to word-of-mouth, 10% were thanks to the book cover, and everything else anyone did for marketing accounted for the final 5% of sales. Word of mouth is clearly pretty huge.

- Viral Marketing: Using preexisting social networks, with an emphasis of the casual, non-intentional and low cost.

Look at those three things: anything there strike you as something a publisher can do better than the author, plus perhaps their first “Ten” people?

((To be fair, there’s no reason at all this doesn’t apply to an author working in Traditional publishing as well. In that case, you want/need your Agent and Publishing Editor to be two of your First Ten, so that they can evangelize within the existing Trad Publishing networks that you-the-author could never reach. That’s obviously valuable, if the option is available to you.))

Now, ponder this: all this marketing theory stuff is not hypothetical. This is something already happening today in one of the publishing niches that has raced ahead of the mainstream publishing genres (fiction, non-fiction) by virtue of never having been part of mainstream publishing in the first place.

I’m speaking of roleplaying game publishing (which you might have guessed from the title of the post). Lemme ‘splain.

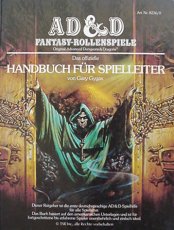

Back in the late 70s and early 80s, roleplaying games were on their first upswing and, since the primary product of the roleplaying gaming industry at the time was books, game developers looked, naturally, to the publishing industry for ideas on how to MAKE books – how to publish.

Back in the late 70s and early 80s, roleplaying games were on their first upswing and, since the primary product of the roleplaying gaming industry at the time was books, game developers looked, naturally, to the publishing industry for ideas on how to MAKE books – how to publish.

And let me tell you, those were some meticulous, geeky bastards back in the day; they figured out how publishing worked and in most cases they followed the traditional publishing model to the letter. Also, they usually aimed for the highest quality products they could (or, often, couldn’t) afford to produce. You should SEE some of the books they turned out – big, beautiful, heavily illustrated, hardbound, double-stitched – you could kill a caribou with the first (or second) edition of Advanced Dungeons and Dragons – don’t even get me started on the original Champions rulebook.

There was, of course, a problem. Roleplaying games are a niche market. Super-niche. The nicheiest. You could have one, probably two, MAYBE three or four product lines successfully pushed into this niche market using traditional publishing methods (each additional line taking a bite out of the success of the other lines) before the niche was full and anything that came after failed. Perhaps not right away, but they’d fail.

TSR (publishers of DnD) was even bought out, and all the others? There is one handful of gaming companies (full-time employing a double handful of people) that have survived from then to now. Meanwhile, the list of those that went under, trying to publish using traditional means, would fill a phone book.

Most people gave it up.

Then came the internet.

With the internet came mailing lists, usenet, and (eventually) forums that in some cases became places of collaboration and creation for that niche market. Some of the early products of that time (FUDGE, to name one) are still popular today, but the basic idea here is that this experience informed some game designers that their ideas had merit, and even an audience.

They just didn’t have any idea how to turn that idea into a PRODUCT without bankrupting themselves. First, the book publishing cost was prohibitive and Second: even if they found an affordable way to publish, how do you get your niche-within-a-niche idea out to the right people?

Then came Dungeons and Dragons 3rd edition, which did a remarkable thing by releasing their rules set as Open Source, basically allowing anyone legal permission to write adventures and source material for the game, and publish it however they like, with one simple caveat: “write it in such a way that the customer still needs our main rulebooks to play.”

Suddenly, the problem with “How do you get your work to the right audience” was gone (provided you wrote stuff for DnD – the biggest product line within Gaming, so not much of a hardship), which left hundreds of creators with only one problem to solve: how to get our work out to people without bankrupting ourselves.

More importantly, this was a group of people who never really associated themselves (mentally) with traditional publishing – they’re gamers, man – so there’s no stigma to the idea of self-publishing. Quite the contrary: in that niche market, self-publishing was the DREAM – a mix of “rock and roll” and “my god, I might actually make some money off this hobby I love!”

Now these were geeky, meticulous bastards (notice a theme?), and when faced with a problem like that, they worked the HELL out of it. By a glorious bit of serendipity, available technology on the internet was finally catching up to their needs at almost the same time: relatively affordable and good-quality print-on-demand, secure and user-friendly online ‘storefront’ software that let you sell electronic files easily. FREE services for acquiring legitimate ISBN numbers and getting listed on sites like Amazon, so that your new DnD module would show up in Amazon searches alongside products from the “big boys.”

Heady times.

When the wave of 3rd edition DnD publishing waned, what was left behind was all that knowledge, experience, creative forums, and the services to make publishing your own stuff possible.

Which is exactly what people did. Today, there are HUNDREDS of products available to this roleplaying gaming niche, and no one ‘going out of business’. Sure, some stuff never sells (because it’s crap), but the good stuff rises – slowly, most of the time – to the top, and finds its target audience, who evangelize and market for those games without much help from the original creator at all, aside from their participation in the social networks surrounding that niche market.

Which is exactly what people did. Today, there are HUNDREDS of products available to this roleplaying gaming niche, and no one ‘going out of business’. Sure, some stuff never sells (because it’s crap), but the good stuff rises – slowly, most of the time – to the top, and finds its target audience, who evangelize and market for those games without much help from the original creator at all, aside from their participation in the social networks surrounding that niche market.

Most of their sales come from:

- Building a presence on social networks and online or virtual communities (The Forge, Story-Games.com, RPG.net, Indie Press Revolution and dozens more, including (of course) Facebook and Twitter).

- Word of mouth, from one successful Actual Play report to the next.

Sound familiar?

Sounds like a real-world example of what people are theorizing indie publishing will look like.

Here’s the thing: indie publishing ALREADY works like the ‘theory’ posits: it’s just that only a small group has realized it so far.

Why all the indie-publishing posts, Doyce?

I’m being interviewed by another writing site in a few days (this one live, via Skype, with someone in Austrailia – it’s is SO COOL to live in the future), and they were kind enough to send me some of the questions they planned to ask, so I could get my thoughts in order. (Good plan, on their part.)

The last question on the list is a doozy: “Why are you still pursuing traditional publishing for Hidden Things when there are so many other options out there today?”

I’ll be biting my tongue not to say “masochism”.

But there’s a flipside to that question, and it goes something like this: “You have a book that was good enough to get representation from an agent, and which you’re (slowly) bringing in line with a publisher’s desires and looking at some success with actually getting the thing published in the traditional market – getting over the threshold, really. Why are you putting so much time into learning about indie publishing?”

Like the header warns at the top of the page, I’m all about my perpetual projects and daily obsessions. The possibilities that exist out there for authors regardless of how they want to get their work out to a reader are definitely one of my obsessions, and as such, it’s one of those things that will continue to get a lot of posting love from me on this blog. Hopefully it’s not boring folks too much; me, I find it fascinating.

I’ve made a living of walking into completely unfamiliar new businesses every couple years, learning said business, then teaching those in the business about how to do it better — that’s how I pay the bills. One of the things I do in those situations is question the standard operating procedures. “It’s done this way because that’s how we do it” is an immediate red flag to me, and the more I learn about how publishing functions today, the more red-flags I see.

In the movie and music industry, the big companies started to focus only on big-money-making projects, and as a result artists that wanted to… you know… do art (or at least their own thing) went independent. The same focus on big-money-makers has been happening within the publishing industry (thanks in part to consolidation of publishing into a half-dozen meta-imprints), but there hasn’t been the same leap to indie publishing. Affordable tools are out there, the quality-in-production is there; authors have the ability to publish, distribute and market books without any involvement from mainstream publishers, thanks to print on demand (POD), e-book technologies, Web 2.0 and the fact that Amazon is now the #2 bookseller in North America and #1 worldwide — but the authors don’t move, because of the stigma of self-publishing.

Yes, before house-consolidations began, publishers were everywhere and there was truth to the idea that an other only self-published if they weren’t good enough to make it ‘legitimately’. This is no longer true, but the characterization of self-published authors as talentless hacks persists.

“It’s that way because it’s always been that way.”

That’s not survival behavior. It’s not even intelligent behavior, which is puzzling, because it’s coming from intelligent people.

I post a lot on this topic right now because I’m trying to figure it out.

Caveat lector.

How to give readers their tree-book fix as an indie author?

Publishing today is a confusing mess of issues. Am I doomed to slave wages as a mid-list author? Worse, will I end up losing money? Does the ‘vanity press’ stigma still exist? If so, does it exist for the reader, or just the publishers? If you’re publishing indie, are you stuck with e-books? If not, what kind of solutions out there? Which ones are ripoffs? How can you get listed with libraries? How can I get my stories out to people who have a book fetish?

It’s an issue that requires a lot of research, and the answers usually lead to more questions (What are my price points? Whose service is really the best deal? What you do you mean ‘it depends’?)

April Hamilton has a great piece up on her blog Indie Author that answers at least some of these questions while comparing venerable Lulu.com to Amazon’s CreateSpace Lulu vs. CreateSpace: Which Is More Economical For The DIY Author?

A quick excerpt:

One advantage of listing your books through Bowkers and Nielsen, whether you do it yourself or let Lulu do it for you, is that doing so makes your books available for order through any retailer, bookstore or library. Personally, I don’t feel indie books receive enough bookstore or library orders to make this worthwhile, but if your motivation is to make your book available to be listed on Amazon.ca, Amazon UK, Barnes & Noble online and even Borders online, it’s probably worth the expense.

As you can see, it’s not all about the price comparisons of the two services, but also a good explanation of what needs to be done to make your POD product function as a proper book in the main venues. April has some great free ebooks on her site that explain the whole process involved in creating your own book, starting with writing the damn thing and taking through through the whole indie publication process, so this doesn’t surprise me.

Penguin demonstrates it can be taught

Penguin Reaches out to Literary Bloggers.

Last week, literary bloggers around the country debated the SXSW Festival’s “New Think for Old Publishers” panel that included Penguin marketing director, John Fagan.

The result was a wake-up call to the publishers on the panel – a debate that was described by my lovely wife as “brutal”. Since then Penguin Group USA has invited bloggers to participate in an online forum to “establish clearer ground rules for how we can best work with the blogging community.”

Simon & Schuster reducing e-book royalties

Simon & Schuster reducing e-book royalties | TeleRead: Bring the E-Books Home.

Doesn’t make any sense.

The main thing publishers do for writers today is handle the complexities of publishing.

The complexities of publishing are vanishing.

The complexities of e-publishing were never there to begin with. What the blue hell do publishers —

How can they justify something like that, based on services provided?

Edit to add: Further info in the comments.

Publetariat Interview: New mediums, Twitter, and storytelling

Last week, I was interviewed by April over at Publetariat about the story I’m telling via Twitter. As one of the central touchstones for the indie publishing movement, she thought the whole idea of creating a story via Twitter — something that would really never transfer to paper in its original format — was interesting, and that’s where our conversation kind of started.

The interview went on for a bit, so it had to be broken into a couple parts, but part one is over here: Twitter As A New Medium In Authorship.

Because it went on a while (and because I’m unforgivably verbose when I get going) some bits had to be left on the cutting room floor, but I’m really happy with the thing as a whole, even if the transitions from one question to the next are a little herky-jerky, due to the necessities of editing.

One piece that makes me sound nearly intelligent:

I think it’s long past time that writers look at new mediums for their work. Paper is just a medium, and as our world (and the smaller publishing world within it) changes, it makes sense for writers to take a look at the tools around us and see if there aren’t some that we overlooked. Artists and sculptors do this sort of thing all the time; “Maybe I can paint on this building, maybe I can make something out of this old car… wait, even better: maybe I can paint on this building with this old car! Genius!” Tom Waits likes to go into hardware stores with a mallet and see what kind of sounds he can find.

What do storytellers use? Spoken words… and paper. That’s it. Very recently, people have considered the still hotly-contested idea of taking the-thing-that’s-on-the-paper and reproducing that exact same thing electronically, and that’s fine, but that isn’t storytelling intrinsically designed for the electronic medium – I mean so intrinsically designed for that medium that it doesn’t actually translate well back to paper or spoken words.

Maybe this story about Finnras is that kind of non-transferable thing – if so, I’m comfortable with that. It’s fun for me and for the people reading it.

The following sentence, which was cut for good reasons, but which I like: “People are trying to take things that were built in/for an electronic medium and force it ‘back’ into a paper format. I’m starting to think ‘maybe you can’t always do that, and maybe that’s okay.'”

Anyway, it was a lot of fun, and got me thinking about things which, frankly, I usually don’t. Parts 2 and 3 go up next week.